KID REPORTERS’ NOTEBOOK

Seeking Justice for Breonna Taylor

In the past year, residents of Louisville have sought justice for the wrongful death of Breonna Taylor, an emergency room technician who was killed by a police officer.

On March 13, 2020, three members of the Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) stormed into the home of Breonna Taylor. The 26-year-old emergency room technician and her boyfriend had been asleep when the officers rammed in the door shortly after midnight. The officers were executing a “no-knock” warrant, a legal order that allowed them to enter the apartment without prior notification.

Taylor’s boyfriend fired his gun, fearing that the intruders were seeking to do harm. The police officers then opened fire, killing Taylor.

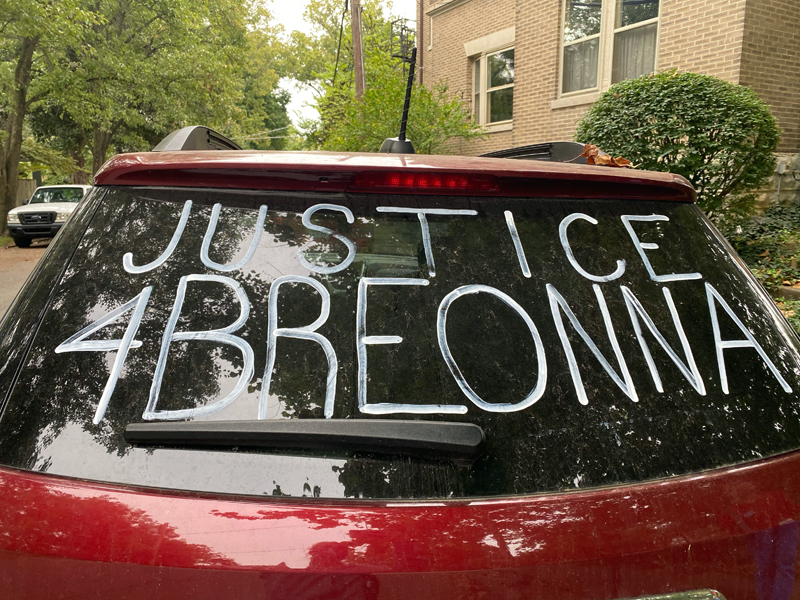

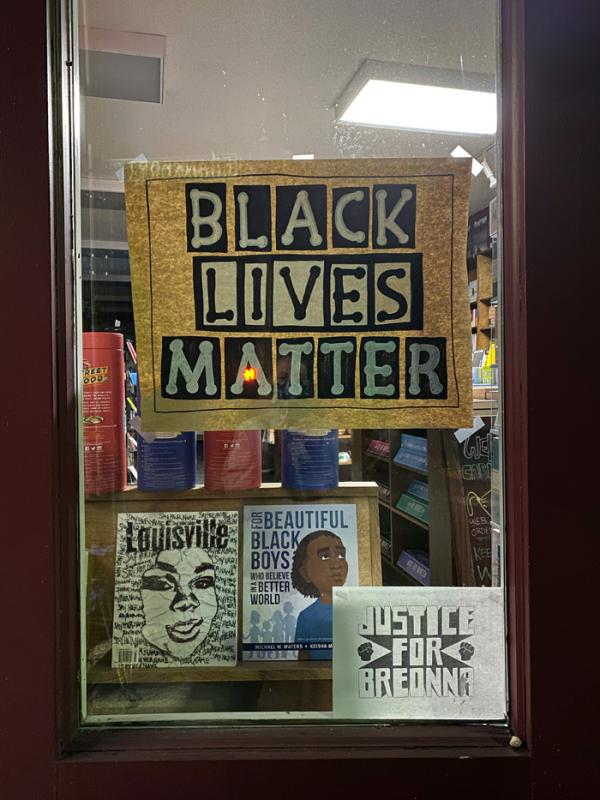

Taylor's death sparked outrage in Kentucky and around the country. From coast to coast, Black Lives Matter protests raised awareness about the racial disparities in police shootings.

In Louisville, Taylor’s family filed a wrongful death suit against the city. As part of the settlement, the city agreed to institute police reforms. The Louisville Metro Council also passed “Breonna’s Law,” which bans the use of no-knock warrants. But one year later, none of the officers has faced criminal charges for Taylor’s death.

The Black Lives Matter movement, which was founded in 2013, has drawn international attention to racial disparities in all aspects of life, including policing.

UNEQUAL JUSTICE

Months after the murder, Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron was assigned to review the LMPD's internal investigation. He convened a grand jury, a group of people who consider criminal charges.

In September 2020, it was announced that the grand jury would not charge any of the officers in Taylor’s death. “According to Kentucky law, the use of force by [two of the officers] was justified to protect themselves,” Cameron said. “This justification bars us from pursuing criminal charges.”

Many residents expressed shock and outrage that no one would be held accountable for Taylor’s tragic death. “The decision was truly heartbreaking,” said Bailey Reed, 16, of Louisville. “We will continue to fight for justice and fairness, not just for our community, but for Breonna.”

Sam Aguiar, the attorney who represents the Taylor family, said that changes are needed in the legal system. “The system of justice for law enforcement is simply not the same as it is for other citizens,” Aguiar told me. “We see this nationwide. Officers get [legal protections that] make them almost immune from any sort of accountability. What kind of message does this send?”

Samuel A. Marcosson, a professor at the University of Louisville’s Brandeis School of Law, agreed. “We need to seek change in the state legislature to pass new and more effective limits on how [police officers] act,” he said.

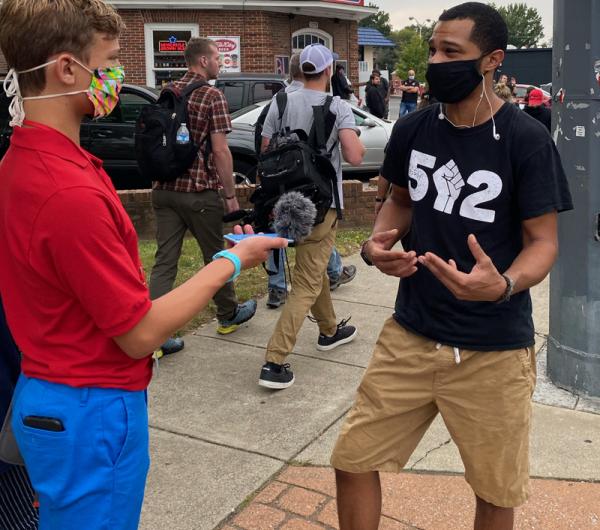

Leo interviews a racial justice advocate at a Black Lives Matter protest in Louisville.

“WORKING TOGETHER”

In October, amid rising frustration in Louisville, retired police officer Yvette Gentry was named interim chief of the LMPD. The first Black women to lead the department, Gentry oversaw internal investigations that led to the termination of Joshua Jaynes, who made untruthful statements related to the no-knock warrant, and Detective Myles Cosgrove, who fired the shots that killed Taylor.

“The divisiveness in our community is not beneficial to anyone,” Gentry told me in January, before stepping down as interim chief. “Please know that good relationships with police are possible, and that we all need to do a better job of talking to each other and being open to working together.”

The city of Louisville has intensified efforts to educate residents about systemic racism. A new exhibit at the Muhammad Ali Center, “Truth Be Told: The Policies That Impacted Black Lives,” explores longstanding racist practices in criminal justice, housing, education, the media, and healthcare.

“We want to highlight many of the policies that have created systemic racism in the United States,” said Donald Lassere, the Ali Center’s president and chief executive officer. The nonprofit museum and cultural organization honors the boxer, civil rights activist, and humanitarian, who grew up in the city.

A memorial for Taylor at Jefferson Square Park in Louisville will get a permanent home at a local museum dedicated to African American history.

“TWO SYSTEMS”

Taylor’s family remains hopeful that justice will be served. “Breonna’s family has done more than fight for her justice,” Aguiar said. “They have been on the ground [across the country], fighting for a system of government that is no longer oppressive, divisive, and bullying in nature. Their efforts, along with those of so many millions of people, cannot stop now. Everyone deserves to be able to wake up each day without the deck stacked against them simply because of skin color.”

Lassere wants young people to get involved in the issues, too. “First, you have to learn, and understand that there are inherent biases in this country,” he said. “Then it’s important that you speak out against racism and racist policies, and understand that there are two systems in this country. If you do that, and speak out against those systems, I think you would be going a long way towards carrying out Muhammad’s legacy.”

When asked what she wants young people to know, Gentry said: “Be hopeful about the future of our community and certainly the possibility for better police and community relationships in the future. I’m happy to be a bridge to building these relationships if you want to work with me.”