KID REPORTERS’ NOTEBOOK

Let Her Fly

WATCH THE VIDEO

Click below to see clips from our Kid Reporters' interview with educator and author Ziauddin Yousafzai.

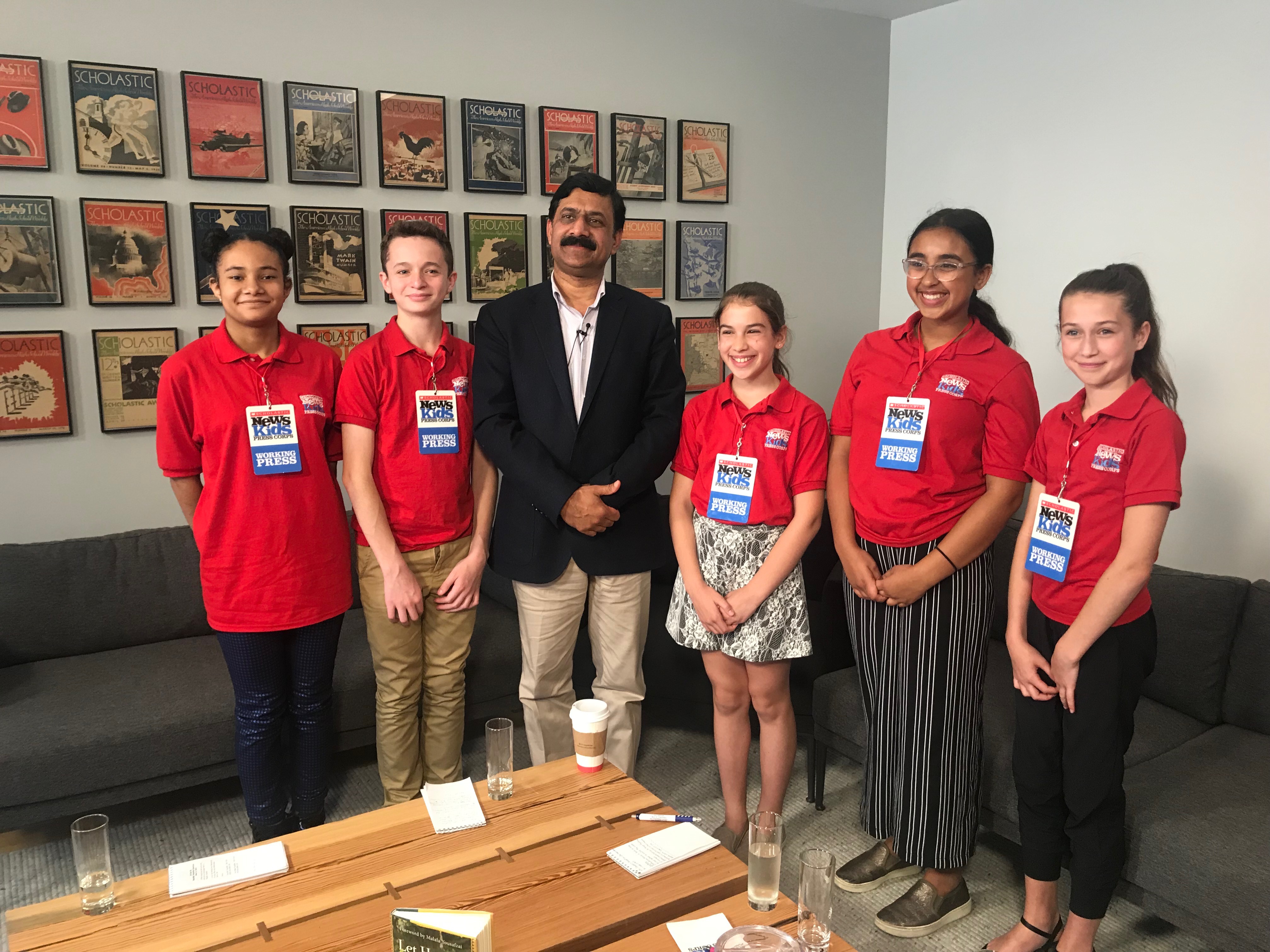

Ziauddin Yousafzai recently visited Scholastic headquarters in New York City to speak with five Kid Reporters. Yousafzai’s memoir, Let Her Fly: A Father’s Journey (Little, Brown and Company, 2018), chronicles his odyssey from a favored son in a patriarchal society to a champion of women’s rights. Born in Pakistan in 1967, Yousafzai is an educator, activist, and author. To the world, he is Malala’s father.

Growing up, Malala bravely stood for the right of all girls to be educated. Because of that, a Taliban gunman shot her in the head in 2012. She nearly died.

Two years later, Malala won the Nobel Peace Prize for her heroism. She was the youngest-ever Nobel laureate. Now a student at Oxford University, she co-founded the Malala Fund with her father. The nonprofit organization supports girls’ education around the world.

Ziauddin Yousafzai, center with Kid Reporters (left to right) Marley Alburez, Josh Stiefel, Liset Zacker, Sunaya DasGupta Mueller, and Amelia Poor

Here are highlights from Yousafzai’s conversation with Kid Reporters Marley Alburez, Josh Stiefel, Liset Zacker, Sunaya DasGupta Mueller, and Amelia Poor. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What would you tell boys and girls to encourage them to respect women?

Education transformed me. It helped my wife and me create and build a family that believes in equality. Through a quality education, our children can learn to respect everyone.

What made you question the treatment of Pakistani women as a child, even though a patriarchal system was the only way of life you knew?

As a child, I didn’t mind being treated as a special person. As I got older, I became more mindful of discrimination. I was a part of a patriarchal society and a patriarchal family.

When you stand against the things you learn through generations, it’s uncomfortable because you’re going against the tide. It’s easy to flow with the tide, but when you go against it, you need boldness and bravery. The first person I needed to convince was me. Once I defeated my old self, I found my new self, who believed in equality.

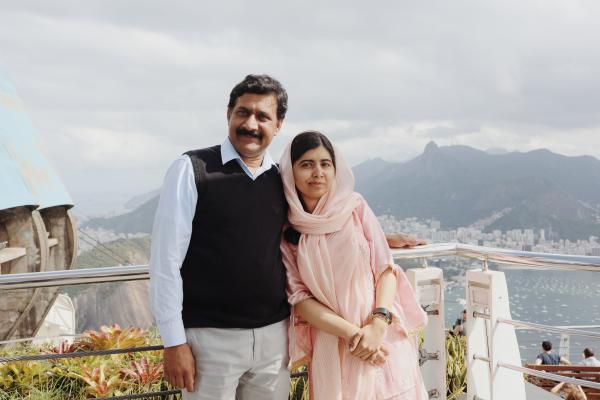

Yousafzai with his Nobel Prize-winning daughter, Malala, in Brazil

Why do you think it took so long for your father to realize the value of women?

My father, like me, grew up in a patriarchal society. In our community, there were many schools for boys but hardly any for girls. So I do not blame my father for not sending his daughters to school. He could have acted differently, but maybe he wanted to be like all the other men in the community. He was more interested in my education. He had big dreams for me, like wanting to see me as a doctor, a very influential person in society. But for his five daughters, his only dream was to get them married as early as possible.

But I’m so grateful for the change that I could see in my father in my lifetime. A man who never thought that about the education of his own daughters, when he saw me as a father very keen about my own daughter’s education, he was inspired. In turn, he became extremely interested in Malala’s education.

What role does education play in helping to achieve gender equality?

Quality education is the most powerful tool. The Malala Fund works in two ways. Number one: Every girl has a right to be educated for a minimum of 12 years, with a free, safe, quality education. When girls complete 12 years of education, they are able to contribute to the community.

If we educated all girls for 12 years, we would add $30 trillion to the economy. We would also help control the global population and fight against child marriages.

Educating girls furthers democracy, peace, and equality, and helps to counter climate change. When girls are educated, we automatically move towards gender equality.

We also need quality education for boys. We have to introduce the kind of curriculum in schools that will help boys fight patriarchal thinking. If education does not teach us equality, there must be something wrong with its quality. When one has a quality education, the values of tolerance, equality, and empathy emerge.

Marley, Amelia, Sunaya, Liset, and Josh after their interview with Yousafzai

What is the most difficult thing about being an outspoken activist?

When you stand for change, people may oppose you and drag you down. Your resilience and bravery come in when you say, “No, I believe in these values. I will stand for them.”

When Malala was 13 years old, she was appearing on television and going to different conferences to speak about education. But it was against the social norms and the traditions of society. My nephew complained to my wife. I told my wife to tell him that he should not focus on our family affairs, and that was the end. Now my nephew is a big supporter of Malala’s mission. If you believe in what you stand for, the world will be with you one day.

How did moving from Pakistan to the United Kingdom affect your views of family life?

It was a big cultural change. I wish that families could be as strong in America and the U.K. as in Pakistan. A couple is a couple, but once a child comes, it becomes an institution and has a responsibility. We have issues in Pakistan, including a patriarchal society, but the family institution is not as strong in the UK.

What are you and Malala doing to further the education of women?

The Malala Fund helps pay for education in countries that do not traditionally provide an education for girls, such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Nigeria. We’re also working to help refugees in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon.

This is Malala’s dream—to see every girl go to school and empower girls to choose their own future. The same girl who spoke for 50,000 girls in the Swat Valley [in Pakistan] is now speaking for 13 million girls around the world.

The Kid Reporters with their mothers at the Scholastic headquarters in New York City

How do you push against sexism, which exists in different ways almost everywhere?

We are seeing a slow and silent change in our communities in Pakistan. In the village where I was born, I did not see any girls going to school. Right now, 250 girls are going to school, and they are getting a very good education. So things change. But still, the struggle continues. I personally think that women and girls, wherever they are, have to come together to win their basic rights.

What advice do you have for parents who want to empower their children?

They should believe in their children. If parents don’t believe in their children, who will? In many societies, we see parents say things that are taunting or discouraging. They don’t know how much that harms a child. A parent should be the first person to believe in a child. When my children did things like give a speech or do their homework, I used to say, “You did fantastic. You are amazing.” Let them know they are special. It’s that simple.