KID REPORTERS’ NOTEBOOK

A Visit to the Thomas Edison Center

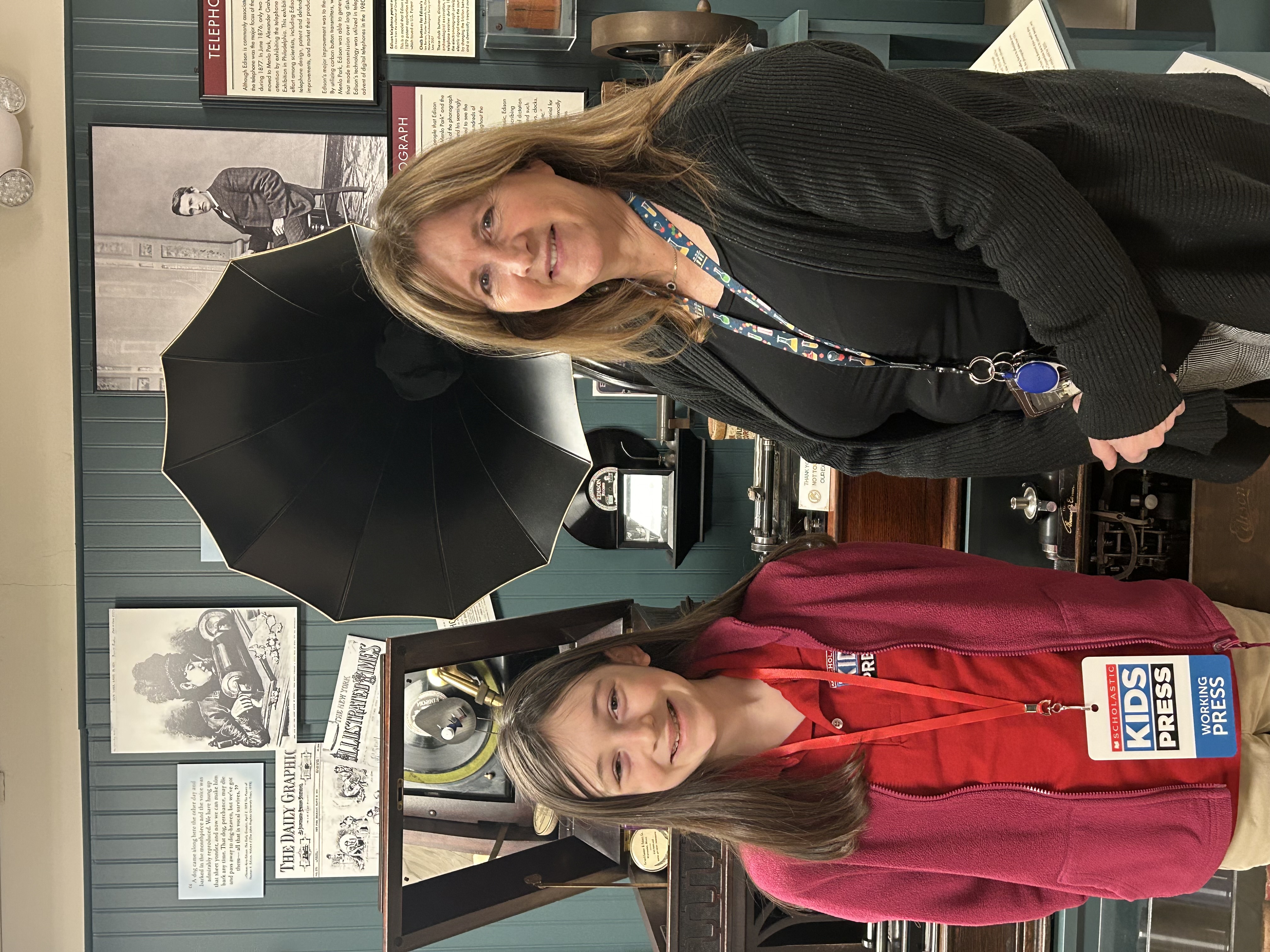

Deirdre visits with Kathleen Carlucci, director of the Thomas Edison Center at Menlo Park. Behind them is a phonograph, one of Edison’s inventions.

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” Those are the words of Thomas Alva Edison, one of the most prolific inventors in the history of the United States.

Edison, who grew up in the Midwest, was largely self-educated. He earned 1,093 patents in his lifetime, including one for the first commercially-viable lightbulb. A prosperous businessman, Edison often reworked existing technology, making it more practical for widespread use.

Edison was born on February 11, 1847, a day that is now celebrated as National Inventors’ Day. In honor of the annual commemoration, I visited the Thomas Edison Center at Menlo Park. Kathleen Carlucci, the center’s director, gave me a tour of the museum. She noted that the seven years Edison spent at the lab he created in New Jersey were his most productive.

“Menlo Park is the birthplace of recorded sound,” Carlucci said. It was in Menlo Park that Edison invented the phonograph in 1877. The invention propelled the 30-year-old Ohio native to international fame. Henceforth, he was known as the “Wizard of Menlo Park.”

A phonograph was the first device to record sound. Carlucci pointed out that it was the precursor to record albums and CDs (compact discs). The original model had no volume knob, so listeners would have to muffle the sound by placing a sock in the machine. That’s where we get the expression “put a sock in it,” which means “stop talking.”

Mark Leschinsky, 17, is following in Edison’s footsteps as an inventor.

“HELPING OTHERS”

Edison died in 1931, but his spirit of ingenuity lives on in young inventors in the Garden State. In 2014, Mark Leschinsky, 17, a student at Bergen County Academies in Hackensack, learned that an Ebola outbreak was devastating West Africa.

“Healthcare workers were risking their lives to try and help patients,” Mark told me. Without adequate protective gear, many doctors and nurses were contracting the virus themselves.

Mark was inspired to act quickly. He got his first patent for a self-disinfecting hazmat suit. The suit is reuseable and can protect workers against any infectious disease, including COVID-19. For his remarkable work, Mark was inducted into the National Gallery for America’s Young Inventors in 2015.

“What really drew me to science and invention was helping other people,” Mark told me. “The feeling that what I make can really help someone . . . drives what I do.”

Like Edison, Mark recognizes that “invention takes experimenting and tinkering,” and lots of failure. “But in the end, it’s very fulfilling to have a final product” that can improve the lives of ordinary people.

For Carlucci, the enduring nature of Edison’s inventions is his greatest legacy. “The things he invented are still in use today,” she said. “They didn’t become obsolete.”

Thomas Edison built a laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, which is now the site of a museum dedicated to his work.