KID REPORTERS’ NOTEBOOK

A Visit to Ellis Island

Between 1892 and 1954, 12 million immigrants arrived at Ellis Island in search of a better life in the U.S.

On a small island just below New York City, I stared up at a massive brick building—the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration. I thought about the 12 million immigrants who were processed there between 1892 and 1954. Most had arrived from European countries by ship. They fled famine, poverty, and political unrest. In some cases, they brought only the clothes on their backs and dreams of a better life in the United States.

During those years, nearly four mllion immigrants came from Italy, according to Stephen Lean, director of Ellis Island’s American Family Immigration History Center. Others came from Eastern Europe in 1917, after the collapse of the Russian Empire.

Today, 100 million Americans can claim an ancestor who came through Ellis Island in New York Harbor. I am one of those Americans.

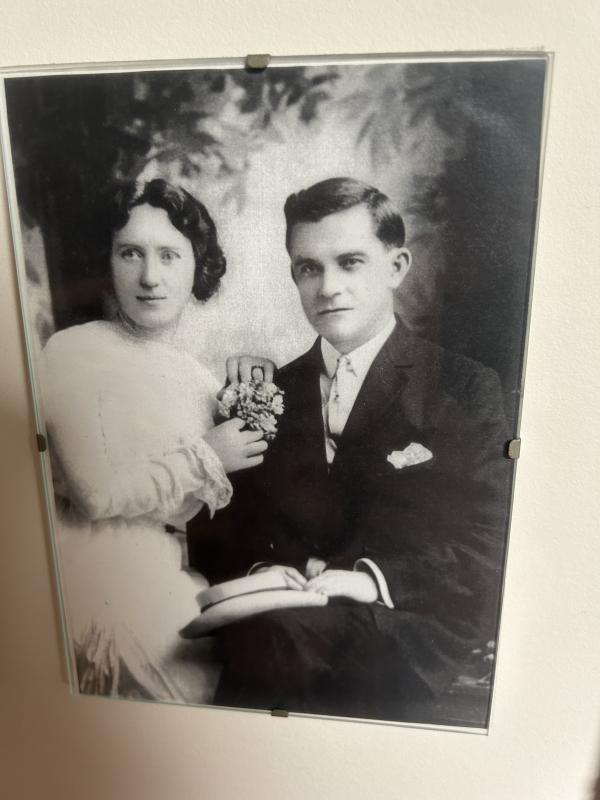

Irish immigrants Michael and Nora Cotter, Deirdre’s great-great-grandparents, are pictured in the early 1920s.

MY IMMIGRANT ANCESTORS

In 1912, my great-great-grandfather, Michael Cotter, left Ireland for a more prosperous life in the U.S. He was 20 years old. By chance, Cotter’s ship departed from Queenstown (now Cobh), where the doomed Titanic had just taken on passengers. Cotter arrived safely in New York City on April 14, the day the Titanic sank.

Cotter later opened a saloon in the heart of New York City. In 1919, it became the first establishment to be raided by the U.S. government. The Wartime Prohibition Act forbade the sale of alcoholic beverages. In a shootout that followed, two men were injured. The clash was covered by The New York Times.

During a visit to my grandparents’ house, I found a photo of Cotter and his wife, Nora Sullivan Cotter, a fellow Irish immigrant. The photo was taken in the early 1920s. After Cotter’s untimely death, Nora was left to raise the couple’s three children. She opened a boarding house for Irish immigrants.

Deirdre at the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration with Stephen Lean, director of the American Family Immigration History Center

FROM AN ABANDONED BUILDING TO A MUSEUM

Ellis Island served as an inspection station until 1924. U.S. officials would make sure immigrants were healthy and able to support themselves before they entered the U.S.

In 1924, a new law limited the number of immigrants who could enter the U.S. Most now had their paperwork processed in their home countries. Ellis Island became a place of detention for the few immigrants who had gotten sick on the boat, had mistakes in their paperwork, or were suspected of being otherwise unfit to enter the country.

On November 12, 1954, the last immigrant being held at Ellis Island was taken from the building, and it was abandoned. Nearly 40 years later, in 1990, Ellis Island was transformed into a historic site. The mammoth restoration, which led to the creation fo the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, was funded entirely by private donations.

Each year, the museum welcomes 3 million visitors. When I visited with my family, I learned that Europe was not the only place of origin for immigrants. People from Asia came through Ellis Island in the 1800s, but in smaller numbers. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 made it more difficult for anyone of Asian descent to stay in the U.S. The act, Lean explained, was an effort by U.S. government officials “to control what it meant to be an American and to control what America looked like.”

Still, many people from Asia worked in the U.S. as laborers, helping to build the new country but getting little credit. In 1943, despite lingering prejudice, exclusionary laws were overturned.

This aerial view of New York Harbor shows Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty, a symbol of freedom for generations of immigrants

TELLING THE STORY OF AMERICA

During Superstorm Sandy in 2012, Ellis Island was flooded and the museum severely damaged. The museum was closed for repairs for a year.

Today, the Ellis Island staff is working on a “re-imagining” process. Their goal is to broaden people’s view of the immigrant story. They want to make sure, Lean said, “that everybody knows their stories are included here. It doesn’t matter if your family arrived in New York or Boston or Galveston, Texas, or San Francisco. It’s a story worth telling.”

I asked Lean what he wanted young people to take away from a trip to Ellis Island. “I want kids to know that regardless of where your family comes from or what your family might look like, somebody who had a family like yours and a story like yours was here on Ellis Island. They made this country what it is today. We’re all standing on their shoulders.”

Check out the Ellis Island website to learn more about the people who came through the center and to plan your own visit.