KID REPORTERS’ NOTEBOOK

Artisans in India Struggle to Gain Recognition

Roopkatha in front of a workshop for artisans in the Kumartuli neighborhood of Kolkata, India

Walking down the narrow, winding lanes of the Kumartuli neighborhood, one is sure to come across sculptors working diligently in small, sometimes rickety, sheds. Kumartuli is in Kolkata, India. Once known as Calcultta, the city is the capital of West Bengal, a state in eastern India. It is also home to a community of more than 400 artisans who are continuing one of India’s ancient traditions.

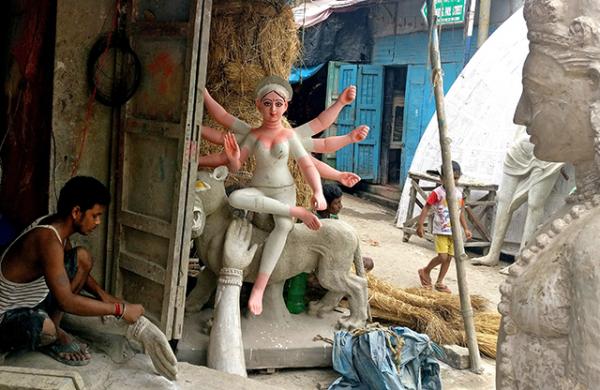

The word Kumar means “to sculpt,” and tuli means “place.” The potters of Kumartuli spend the entire year sculpting effigies [models] of Hindu gods for various religious festivals. The idols are life-size, with intricate detailing. The techniques used to create them have been passed down from generation to generation and are fiercely-protected family secrets.

“The first step is to build a basic straw-and-bamboo framework of the effigy,” says Haru Pal, a Kumartuli artisan. “Then we coat it with entel mati, a special type of clay deposited along the Hooghly [WHO-glee] River Bank.”

A sculpture of Durga, a Hindu goddess, that was carved by Ramesh Pal

Haru works beside family members, but none of the individuals quoted in this article are related to him. The name “Pal” was given long ago to members of Indian society who were artisans. Eventually, it became a surname. By tradition, the craft was taught to brothers and sons. Today, some women are sculptors, too.

“GIFTING EYESIGHT”

The best time to visit Kumartuli is between March and late August. That is when artisans are sculpting idols of Durga, a Hindu goddess, and her children for Durga Puja. Durga Puja is a major Hindu festival celebrated for 10 days each year, typically in late September.

“Each complete figure takes almost three months to make,” explains potter Naresh Chandra Pal. “The senior-most sculptor in the family then performs Chokkhu-Daan, which literally means gifting eyesight.” A potter paints the idol’s eyes, which, according to popular belief, symbolizes breathing life into it. Most idols are more than 10 feet tall.

“Idol-making forms a large part of India’s slowly-dying artistic and cultural heritage,” says Haru Pal. “This makes [the tradition] even more important.”

An artisan sculpts the hand of an effigy in the labyrinthine streets of Kumartuli.

NOT ENOUGH APPRECIATION

Despite their talents, most of these artisans remain largely unknown in India. Families live in crowded tenements by their workshops. Women still drape clothes on makeshift wash lines across roads.

“The younger generation is unwilling to make idol-making their profession,” says Ramesh Pal. “We are neither appreciated enough nor given a proper income.”

The government has promised to build modern housing and renovate the workshops in Kumartuli. A community art studio is also planned. “However,” Ramesh says, “the government has yet to fulfill these promises.”

Editor's note: All quotes have been translated from Bengali into English by the author.