KID REPORTERS’ NOTEBOOK

Watch Us Rise

Marley with authors Ellen Hagan (left) and Renée Watson at the launch of their new book, Watch Us Rise

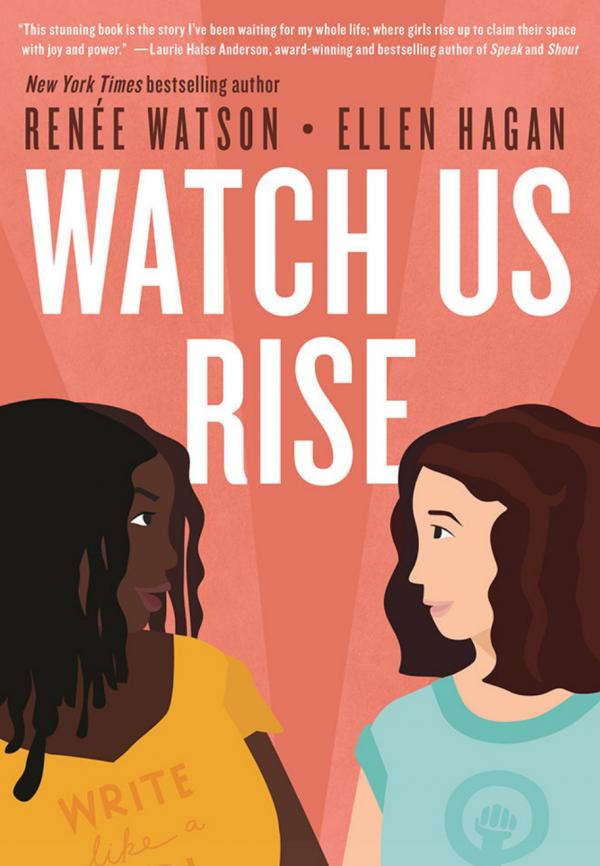

Authors Renée Watson and Ellen Hagan have teamed up to create Watch Us Rise, a new novel from Bloomsbury. The thought-provoking book follows two young friends, Jasmine and Chelsea, who start a club to talk about issues they face at their New York City high school.

Watson is the author of Piecing Me Together, This Side of Home, and What Momma Left Me, among other titles. She has earned a Newbery Honor and Coretta Scott King Award for her work. Hagan, who is a writer, performer, and educator, is the author of the poetry collections Hemisphere and Crowned.

At a recent celebration of Watch Us Rise at the I, Too, Arts Collective in Harlem, I spoke with Watson and Fagan. Here are highlights from our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity:

What inspired you to write Watch Us Rise?

Watson: I wanted to collaborate with [Ellen], and work on a project that talked about all the things we talk about in our real lives.

What issues did you want to make your readers aware of?

Hagan: We wanted young people to feel like they could rise up and figure out what kind of world they wanted to live in.

Watson: Our book is based on friendship, on a crew of young people who care about each other. They’re all artists. They’re figuring out who they are, how to use art to speak back to the world, and how to create the world they’re searching for. They’e pushing back against racism and sexism and talking about women needing the space to use their voices.

Watch Us Rise explores the friendship between Jasmine and Chelsea, who decide to do something about the way women are treated at their New York City high school.

Why are the messages in the book important for young adults?

Watson: When you’re young, people are always speaking for you, or on behalf of you. When I was young, there were a lot of statistics about girls like me: girls from my neighborhood, girls who went to my school, black girls, girls who were growing up in a single-parent home. It’s important for young people to tell their own story about who they really are.

How did you come up with the characters of Jasmine and Chelsea?

Watson: The young people I’ve worked with are really who Jasmine is based on. She’s a mix of several different people I mentored when I was a teaching artist.

Hagan: Chelsea has a lot of passion and energy, some of which gets her in trouble. She uses poetry as an outlet. I used poetry when I was in middle and high school as a safe space. I had my journal, and it was something I went back to, to remember what was happening in my life, and how to navigate those emotions and feelings. Just like Chelsea, I was often going back to my journal and figuring out who I was.

“I want young people to find their place and figure out what they want to say,” says award-winning author Renée Watson.

What was your collaboration process like?

Hagan: When Renee made the suggestion to write something together, I was excited to learn from her and be in the same room to create together. I also had a good feeling about us being able to have discussions and get an idea for the book. We created a timeline, worked in my apartment, her apartment, or cafés. We did a lot of piecing it together from there.

Watson: Writing is so solitary. You’re by yourself a lot. For me, It was a joy to have somebody to bounce ideas off of, and when I was stuck, to have someone help me get unstuck, which is something I normally don’t have when I’m writing a novel. It was really great to have a partner.

What discussions do you hope to spark among readers of the book?

Watson: I hope young people start to think about what they want to say and what’s happening in their immediate world, but also what's happening nationally and internationally. What are the things that you care about, and what do you want to say about them? Are you going to use art or be a reporter? I want young people to find their place and figure out what they want to say.

Hagan: What I loved about writing the book, and putting the resources together in the back of the book, is figuring out how much history there is on these subjects, and how I can add my voice to those layers.

What issues did you not get to address?

Watson: The book is about these two girls, Jasmine and Chelsea, and their world. There are so many other stories that need to be told, that I hope get told. We were trying not to do too much, because then it wouldn’t feel genuine. We focused on racism, sexism, and body shaming. There are so many things under those umbrella words, so we had to make sure that it felt true to the characters.

The I, Too, Arts Collective, which Watson founded in 2016, was once the home of poet Langston Hughes, a leader of the Harlem Renaissance.

How do you talk about sensitive topics without offending people?

Watson: I don’t know that you do. When I’m talking as Renée, telling my truth, it’s mine. I am clear on saying: This is what I think. This is what I have experienced.

I know there will be a point where a character offends a reader. I hope that I’m able to listen to feedback and take it in. I don’t go into writing trying to offend anyone, but I’m also not thinking about that, because if I think about it too much, then I’m writing for people and not being true to the story.

Hagan: As a teacher I often think of sensitive topics, issues, and themes that we’re talking about as a group. I think: How do I create a safe space for people to share who they are? It's figuring out, how to get people to be in a dialogue and community with each other. The more I have a safe space and community, the more I might feel very vulnerable talking about sensitive issues. But I know the vulnerability is because I care about the topic deeply, and I trust that I’ve created a space where everyone can be vulnerable.

Watson: When I was your age [12], I lived in Portland, Oregon. There was so much happening, but none of the adults were talking about it. When you see blatant racism or sexism, and no one is acknowledging that it’s real, you start to second-guess yourself. You ask such questions as: Am I making it up? Am I too sensitive. Why am I the only person who cares?

I hope that our work is a place where young people say: I see this, too, at my school, or in my neighborhood, and I want to talk about it.

What role do adults play in helping children understand—or not understand—these issues?

Hagan: Because I have daughters, I think a lot about how we not just consume media, but read it. By that I mean making such observations as: There aren’t that many people of color on this TV show, or I don'’ like the way the people of color are represented. Or what do all the princesses look like? Is their body type the same, their hair, the color of their skin? I’m always thinking about how to expose these things and address all them with my daughters so that they can think about it for themselves.

Watson: I’m unlearning things that I was taught as a child. It’s easy to pass those things on to the younger generation. Hopefully, intergenerational conversations are happening where we can all sit at the table and say: This is what I learned about beauty. What are you learning about beauty? Adults could play a big role in getting people together to facilitate these conversations.

Do you have any words to inspire adult women?

Hagan: I feel lucky that we have a collective of women, representing all different art forms, who inspire and shape and change us. Find your people, find your community, and do celebrations together.