KID REPORTERS’ NOTEBOOK

King Tut: Journey Through the Underworld

WATCH THE VIDEO

Click below to see clips from Benjamin’s interview with Diane Perlov, senior vice president for exhibits at the California Science Center.

King Tutankhamun (too-tahn-kah-men) ascended to the Egyptian throne in the 1300s B.C. He was only about nine years old. After the young pharaoh’s death, less than a decade later, Tut was largely forgotten.

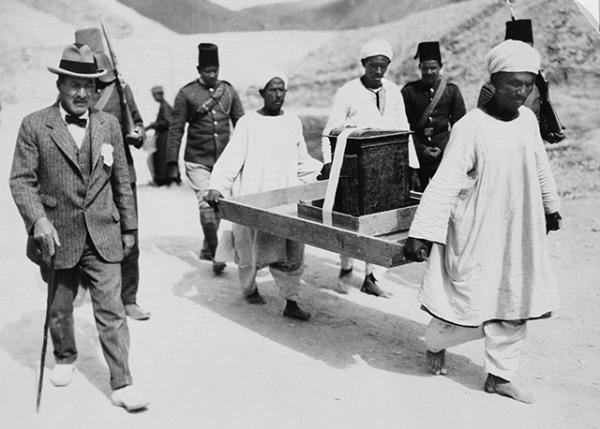

Then, in November 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter made a stunning discovery—Tut’s gilded burial place in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings.

To celebrate the upcoming 100th anniversary of Carter’s discovery, the California Science Center in Los Angeles is presenting a blockbuster exhibit: “King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh.”

The exhibit includes priceless artifacts that have never left Egypt. After the tour, many of these fragile objects—including games, jewelry, and a burial mask that is world-famous—may never leave the Mediterranean country again.

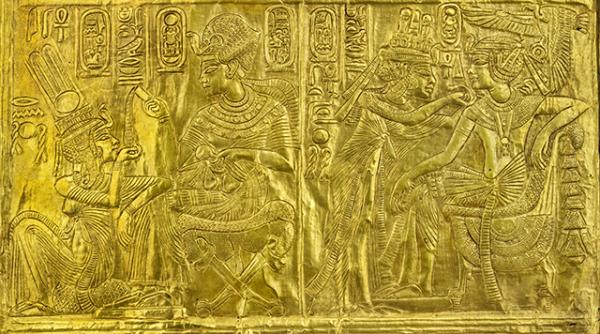

A gilded wooden shrine shows scenes of King Tut with his wife, Ankhesenamun, who was also his half-sister. (Photo by Laboratoriorosso, Viterbo, Italy)

“AN OVERNIGHT CELEBRITY”

On a recent visit to the Science Center, I spoke with Diane Perlov, senior vice president for exhibits. The young pharaoh was unremarkable during his reign, said Perlov, who has a Ph.D. in Anthropology.

“The only thing that made King Tut famous was the discovery of his tomb,” Perlov said. “It was resplendent with more than 5,000 burial objects. That just made King Tut an overnight celebrity.”

The artifacts shed light on ancient Egyptians’ beliefs about life and death. Murals found on the walls of the burial chamber show that Tut was expected to embark on a journey through the underworld after his death, culminating in a happy afterlife. Many of the objects were meant to protect, comfort, and entertain him.

British archaeologist Howard Carter walks beside Egyptians as they carry an artifact from Tut’s tomb. “It was a sight surpassing all precedent, and one we never dreamed of seeing,” Carter said about the discovery.

NOT YOUR PARENTS’ KING TUT

Perlov, who traveled to Egypt to handpick more than 150 artifacts, described what is unique about this exhibit. “Visitors go through the underworld with King Tut,” she said. The journey consists of three phases: preparation, danger, and rebirth. The exhibit is arranged in that order.

Technological advances allow visitors to learn much more about Tut’s life, death, and family tree than blockbuster exhibits of the 20th century.

CT scans, for example, indicate that a hole in Tut’s skull, previously thought to be evidence of murder, actually occurred after his death. DNA analysis now points to malaria as the possible cause of the pharaoh’s death.

“King Tut is a fascinating story,” Perlov said, “and this exhibit shows how modern science and technology can reveal new information about the past.”

The exhibit runs through January 6, 2019.